Electrons inside labs at MIT can behave in really strange ways. When forced through a special sieve they come out with a fraction of the charge they had going in. Under traditional physics models, that should be impossible. The charge on an electron is so stable that it’s been considered a physical constant called “e.” When quantum physics came along, Quarks confused everyone by being 1/3 e but that works out alright because they’re always found in threes. MIT made a breakthrough by creating other fractions of e. Better yet, they created a rare and elusive “fractional quantum Hall effect” at room temperature, without any phenomenally huge magnetic fields.

Electrons with a twist

The fractionally charged electrons produced at MIT are so revolutionary it creates a new field of study called “twistronics.”

MIT professor of physics Senthil Todadri explains, “this is a completely new mechanism, meaning in the decades-long history, people have never had a system go toward these kinds of fractional electron phenomena.”

That, he insists, is “really exciting because it makes possible all kinds of new experiments that previously one could only dream about.” It all started when the MIT research team began beaming electrons through “pentalayer graphene.” Graphene is a sheet of carbon atoms a single molecule thick.

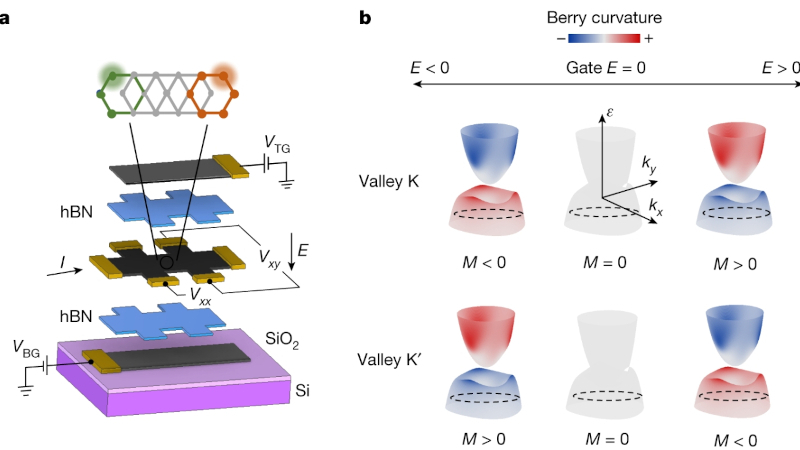

It creates a “chicken wire” like lattice of hexagons. The team stacked five of these layers on top of each other with a small gap in between each layer. Also they twisted each layer at a slight angle to the layer below.

As soon as they fired up their experiment, it produced results they didn’t expect. After finding the mistake in their mathematical model, what they were seeing in experiments made perfect sense. They were astounded.

Their work suggests that the interactions of electrons “in confined two-dimensional spaces lead to novel quantum states.” Their big mistake was running the calculations for one electron at a time. In real life, there is more than one electron passing through the graphene layers and they all react with each other on a quantum level.

Split the charge

Todadri’s team has “made significant progress in understanding how electrons can split into fractional charges.” Even so, they couldn’t have done it without previous work by MIT Assistant Professor Long Ju.

His group was the first to discover “that electrons seem to carry ‘fractional charges’ in pentalayer graphene.”

Quantum physicists were already aware that “electrons can split into fractions under a very strong magnetic field, in what is known as the fractional quantum Hall effect.”

That’s how the easier graphene method picked up a more complicated name. The layered carbon approach produces the “fractional quantum anomalous Hall effect.” Anomalous because there’s no hefty magnetic field required to produce it.

When “each lattice-like layer of carbon atoms is arranged atop the other and on top of the boron-nitride,” it “induces a weak electrical potential. When electrons pass through this potential, they form a sort of crystal, or a periodic formation, that confines the electrons and forces them to interact through their quantum correlations.”

“This electron tug-of-war creates a sort of cloud of possible physical states for each electron, which interacts with every other electron cloud in the crystal, in a wavefunction, or a pattern of quantum correlations, that gives the winding that should set the stage for electrons to split into fractions of themselves.“